Celebrating Black Legal Trailblazers:

Their Impact on the Justice System

In honor of Black History Month, this blog will dive deep into the pivotal role African American lawyers have played in shaping the legal landscape of our nation. We will explore the struggles, resilience, and unwavering dedication of Black voices who faced immense challenges, both inside and outside the courtroom, to break barriers and fight for justice. From the early pioneers who challenged segregation laws to the modern-day advocates pushing for civil rights and equality, these trailblazers have left an indelible mark on the legal system.

Edith Peterson Mitchell: 1941 – 2024

We start off with a very special woman in black history. Edith Mitchell is cousin of our very own receptionist, Rhonda Williams. Edith, known as Faye by her family, decided to become a doctor after visiting a local black doctor in the late 1950’s. She was a little girl during segregation and went with her sick grandfather to the only black doctor in the area. Due to racial tensions at the time including segregated hospitals black families lacked quality medical assistance. The only local black doctor was unable to treat her grandfather’s illness so she announced to her parents that she would become a doctor when she grew up. Her resolve did not waiver as she became older. During segregation she attended Tennessee State University. In 1971, she enrolled at Medical College of Virginia in Richmond, later named Virginia Commonwealth School of Medicine. Mitchell was the first black student to graduate from VCU’s 3 year program. However, her time in medical school was not without racial hurdles. She recalls a time during her sophomore year in 1972 while being fitted for her white coat, a seamstress asked, “Are you going to like working in the kitchen at the hospital?” “I was there to get my white coat, and they offered me a white dress.”

She completed her internship and residency in internal medicine at Meharry Medical College and became a hematologist at Andrews Air Force Base. She was an Air Force flight surgeon and was the first female physician in the Air Force, Air Force Reserve, or Air Force National Guard to be promoted to brigadier general. Upon retiring from the USAF she joined the faculty of medicine and medical oncology at Thomas Jefferson University. In 2009 she was the recipient of the American Cancer Society Control Award for her research in pancreatic and colorectal cancer.

In 2012 she earned the American Society of Clinical Oncology Humanitarian Award for providing patient care through innovative means or exceptional service or leadership in the United States or abroad. She was the first black woman to receive the PHL Life Sciences Ultimate Solution Award. She was the Editor in Chief of the Journal of the National Medical Association.

Even with all of her numerous and great accomplishments Cousin Edith had a great and steadfast love for family. It is with fond remembrance of our last family reunion at my father’s house prior to his passing that she brought a scrap book of family photos that she had saved over many years and compiled in a huge scrap book that we all gathered around and enjoyed.

Her accomplishments were so numerous that they cannot all be listed, but they will live on in the history of this nation.

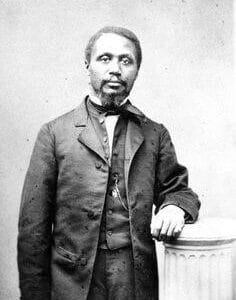

James Alexander Chiles: 1860 – 1930

J. Alexander Chiles, a native of Richmond, VA, was part of a large family with eight children, including his twin brother John R. Chiles. John played a pivotal role in supporting J. Alexander’s educational pursuits, providing financial assistance that enabled him to attend both Lincoln University in Pennsylvania and the University of Michigan Law School. This familial support was instrumental in shaping J. Alexander’s future legal career.

In 1890, J. Alexander Chiles relocated to Lexington, KY, where he established a prosperous law practice at 304 W. Short Street. While James W. Schooler holds the distinction of being the first African American lawyer admitted to the Fayette County Bar in 1888, it was Chiles who made history in 1890 as the first African American attorney to argue a jury case in Lexington. This achievement underscored Chiles’s significant contribution to the legal landscape of the city. In the same year, Chiles also became a notary public, further expanding his professional role within the community.

One of Chiles’s notable cases involved representing Anthony Duncan, who was accused of murdering Dr. Gorham. This case highlighted Chiles’s commitment to providing legal representation to those in need. By 1907, Lexington boasted four African American lawyers, including Chiles, who continued to play a crucial role in advocating for justice and equality. Chiles’s impact extended beyond local courts. He argued a Supreme Court case against the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad, challenging the segregation of railroad coaches. This landmark case stemmed from Chiles’s own experience of being forcibly removed to the “Colored” coach despite holding a first-class ticket from Washington D.C. to Lexington. Chiles’s legal action against the railroad company demonstrated his unwavering dedication to fighting for civil rights and challenging discriminatory practices.

In addition to his legal career, Chiles was deeply involved in Lexington’s Colored Seventh Day Adventist congregation. He served as a trustee, deacon, and treasurer of the first church, which was constructed in 1906 at the corner of Fifth and Upper Streets. Chiles’s wife, Fannie J. Bates Chiles, also played an active role in the church, serving as the first librarian. The church, led by Elder Alonzo Barry, was a cornerstone of the African American community in Lexington, and the Chiles family’s involvement reflected their commitment to faith and community service.

In 1910, James and Fannie Chiles contemplated moving from Lexington to Richmond, VA, but ultimately decided to remain in Lexington. They were listed as residents of Lexington in the 1930 U.S. Census, indicating their continued presence in the community. However, James Alexander Chiles passed away in Richmond, VA, in April 1930. Despite his death in Richmond, Chiles’s legacy as a pioneering lawyer and civil rights advocate in Lexington remained a significant part of the city’s history.

Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander: 1898 – 1989

Born into a family that valued education, Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander excelled academically from a young age. Despite facing significant discrimination and prejudice due to both her race and gender, she persevered and pursued higher education. Her journey was fraught with challenges, but her determination and intellect propelled her forward.

At the University of Pennsylvania, Alexander faced numerous obstacles. She encountered poor advising, was falsely accused of plagiarism, and even had her intellectual property stolen by other students. These experiences would have discouraged many, but she remained focused on her goals. In 1919, she earned her master’s degree in economics, becoming the first African American woman to do so at the University of Pennsylvania. Her academic achievements did not go unnoticed, and she was awarded the prestigious Francis Sergeant Pepper fellowship. This fellowship provided her with the financial support to continue her studies, and in 1921, she earned her Ph.D. in economics, becoming only the second African American woman in the United States to achieve this feat.

Alexander’s thirst for knowledge and her commitment to social justice led her to pursue a law degree. In 1927, she graduated from the University of Pennsylvania Law School, becoming the first Black woman to do so. She was also the first Black woman admitted to the Pennsylvania Bar, paving the way for countless others to follow in her footsteps.

Her pioneering spirit extended beyond academia and the legal profession. In 1919, she was elected the first national president of Delta Sigma Theta sorority, a position she held until 1923. During her tenure, she expanded the sorority’s reach and launched its first national program, demonstrating her leadership abilities and her commitment to community service.

After law school, Alexander joined her husband’s law practice, where she specialized in estate and family law. However, she also remained actively involved in civil rights law, using her legal expertise to fight for equality and justice. In 1928, she was appointed as Assistant City Solicitor for the City of Philadelphia, becoming the first African American woman to hold this position. Throughout her career, Alexander tirelessly advocated for civil rights and social justice. She challenged discriminatory laws and practices, fought for equal opportunities for all, and used her voice to speak out against injustice. Her work helped to shape the course of the Civil Rights Movement and paved the way for future generations of activists.

Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander’s legacy is one of perseverance, intellect, and unwavering commitment to social justice. She broke down barriers, shattered stereotypes, and inspired countless others to follow in her footsteps. Her contributions to academia, law, and civil rights activism continue to resonate today, and her story serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of fighting for equality and justice for all.

Macon Bolling Allen: 1816 – 1894

Born Allen Macon Bolling in 1816 in Indiana, he was a free man who taught himself to read and write. His first job was as a schoolteacher, where he continued to improve his literacy skills. In the early 1840s, Bolling moved to Portland, Maine, and changed his name to Macon Bolling Allen. There, he befriended General Samuel Fessenden, a local abolitionist and attorney who had recently opened a law practice. Allen became Fessenden’s apprentice and law clerk. By 1844, Allen was proficient enough in law that Fessenden introduced him to the Portland District Court and recommended that he be allowed to practice law. His request was denied because he was not a citizen, although Maine law allowed anyone with “good moral character” to be admitted to the bar. Allen decided to take the bar exam and was admitted to practice law in Maine on July 3, 1844, after passing the exam and earning his recommendation. He was also declared a citizen of Maine.

Finding work in Maine as a Black lawyer was difficult because few Black people lived there and White people were generally unwilling to hire a Black attorney. Consequently, Allen moved to Boston, Massachusetts, in 1845, where he met and married his wife Hannah. The couple had five sons, most of whom became teachers.

Allen passed the Massachusetts bar exam on May 5, 1845. Shortly after, he and Robert Morris, Jr. opened the first Black law office in the United States. Allen’s ambitions did not stop there; in 1848, he passed another rigorous exam to become Justice of the Peace for Middlesex County, Massachusetts. He is believed to be the first Black man to hold a judicial position.

After the Civil War, Allen moved to Charleston, South Carolina, to open a new legal practice. He was appointed as a judge in the Inferior Court of Charleston in 1873 and elected as a probate judge for Charleston County, South Carolina, in 1874.

After Reconstruction, Allen moved to Washington, D.C., where he worked as an attorney for the Land and Improvement Association until his death in 1894 at age 78. He was survived by his wife and one son, Arthur.

Charlotte E. Ray: 1850 – 1911

In the 19th century, the legal landscape in the United States was a bastion of white male privilege, systematically excluding women and people of color from its ranks. The barriers to entry were high, and the prevailing societal norms reinforced the notion that law was not a domain for those deemed “other.” Yet, amidst these formidable obstacles, Charlotte E. Ray emerged as a beacon of hope, shattering stereotypes and becoming the first Black woman lawyer in the United States.

Ray’s journey into the legal profession was deeply influenced by her father, an ardent abolitionist who instilled in her the importance of education and social justice. Recognizing her intellectual prowess, he encouraged her to pursue higher learning, a path that was fraught with challenges for a Black woman in the 19th century. Despite limited opportunities, Ray persevered, ultimately gaining admission to Howard University, an institution that, unlike many others at the time, did not discriminate based on race or gender.

Ray’s legal education at Howard was rigorous and demanding, but she excelled in her studies. The details surrounding her admission to the bar remain shrouded in some mystery, but in 1872, she achieved the remarkable feat of becoming a licensed attorney in the District of Columbia. This accomplishment was not only a personal triumph but also a significant milestone for Black women and the legal profession as a whole.

However, Ray’s groundbreaking achievement did not translate into a thriving legal career. The pervasive racism and sexism of the era proved insurmountable. Potential clients, steeped in prejudice, were reluctant to entrust their legal matters to a Black woman, and the legal establishment offered little support. Despite her best efforts, Ray struggled to secure a sustainable practice and was eventually forced to close her office.

Undeterred by these setbacks, Ray continued to champion the causes of social justice and equality. She became a vocal advocate for women’s suffrage, recognizing the interconnectedness of the struggles for racial and gender equality. She also remained committed to education, working as a teacher and inspiring countless young people to pursue their dreams.

Ray’s story is a testament to the resilience and determination of Black women who dared to challenge the status quo in the face of overwhelming adversity. Her pioneering spirit paved the way for generations of Black women lawyers who followed in her footsteps. However, her struggle also highlights the enduring challenges of achieving true diversity and inclusion in the legal profession.

Even today, the legal field continues to grapple with issues of representation and equity. While progress has been made, minority women remain underrepresented in leadership positions and continue to experience a significant wage gap compared to their white male counterparts. The legacy of Charlotte E. Ray serves as a poignant reminder that the fight for equality in the legal profession is far from over. It is a call to action for all those who believe in a just and equitable legal system where every individual, regardless of race or gender, has the opportunity to succeed.

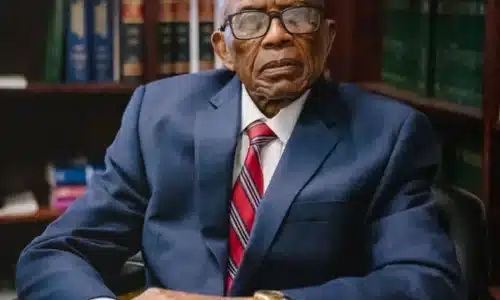

Fred Gray: 1930 – Present

Born in 1930, Gray’s intellectual curiosity and academic aptitude were evident from a young age. He began his formal education at the tender age of five, skipping several grades due to his advanced abilities. He later attended the Nashville Christian Institute, where he excelled academically and honed his oratory skills, setting the stage for his future as a powerful advocate.

Although Gray initially intended to become a history teacher and preacher, fate had other plans. Encouraged by mentors and recognizing the pressing need for legal representation in the fight for equality, he shifted his focus to law school. At the age of 23, Gray graduated from Western Reserve University Law School, equipped with the legal acumen and passion for justice that would define his career.

Upon returning to Montgomery, Gray wasted no time in fulfilling his pledge to challenge the entrenched system of segregation. His legal career took off when he represented Rosa Parks, who had been arrested for refusing to give up her bus seat to a white man. Gray’s involvement in the subsequent Montgomery Bus Boycott solidified his reputation as a fearless advocate for civil rights. He served as a legal advisor to the boycott’s leaders and played a pivotal role in the landmark Supreme Court case Browder v. Gayle, which led to the desegregation of city buses.

Gray’s legal battles extended far beyond the Montgomery Bus Boycott. He defended Martin Luther King Jr. against trumped-up tax evasion charges, represented students who had been expelled from Alabama State College for their activism, and filed a class-action lawsuit on behalf of marchers who had been brutalized in Selma. His work also reached the Supreme Court in cases like Gomillion v. Lightfoot, where he successfully challenged racial gerrymandering in Tuskegee.

Gray played a crucial role in dismantling segregation in Alabama’s schools. He represented students seeking admission to the University of Alabama and Auburn University, and his lawsuit, Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, resulted in the integration of all educational institutions in the state. Gray’s advocacy also extended to the victims of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, a shameful chapter in American history where Black men were denied treatment for syphilis so that researchers could study the disease’s progression. Gray’s tireless efforts led to a $10 million settlement and medical treatment for the study’s survivors.

Gray’s contributions to the Civil Rights Movement have earned him numerous accolades, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. His unwavering dedication to justice and equality has inspired countless others to take up the mantle of advocacy and continue the fight for a more just and equitable society. Fred Gray’s legacy as a civil rights champion will forever be etched in the records of American history.

Written by: Rhonda Williams and Kaylin Shackelford

Rhonda Williams is a receptionist here at Barrow Brown Carrington. Rhonda brings a warm, professional demeanor to all client interactions. She is always ready with a smile and ensures that every client feels heard and supported from the moment they walk in the door

Kaylin Shackelford is our Web and Social Media Specialist. She has a passion for data and creativity. Kaylin uses her experience to understand how to connect the Barrow Brown Carrington brand with their clients across all platforms.

Request A Consultation

Submitting your information does not create an attorney-client relationship.

DISCLAIMER

THE INFORMATION PROVIDED IN THIS POST IS FOR GENERAL INFORMATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY AND DOES NOT CONSTITUTE LEGAL ADVICE. LAWS AND REGULATIONS VARY BY STATE, COUNTY, AND SPECIFIC CIRCUMSTANCES OF YOUR MATTER, AND THE INFORMATION PRESENTED HERE MAY NOT APPLY TO YOUR PARTICULAR SITUATION. ALWAYS CONSULT WITH A QUALIFIED FAMILY LAW ATTORNEY TO OBTAIN ADVICE TAILORED TO YOUR INDIVIDUAL CIRCUMSTANCES. REVIEWING THIS BLOG POST DOES NOT CREATE AN ATTORNEY-CLIENT RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN YOU AND THE AUTHOR, PUBLISHER, BARROW BROWN CARRINGTON, PLLC OR ITS ATTORNEYS. THE AUTHOR AND PUBLISHER ARE NOT RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY ACTIONS TAKEN BASED ON THE INFORMATION PROVIDED IN THIS BLOG POST.

IF YOU HAVE LEGAL QUESTIONS PLEASE CONTACT OUR OFFICES DIRECTLY FOR A CONSULTATION IN COLORADO, FLORIDA, INDIANA, KENTUCKY, OR OHIO.